Students in an academy should have a steady diet of activities that inspire them. There are a number of ways this can be accomplished. Inspirational activities should be employed at the school level by building administrators during assemblies, morning announcements, and other times when students are assembled. Inspirational activities should also be employed by classroom teachers as transitional activities, short breaks, and other times deemed appropriate by the teacher.

Movies

Movies can be inspirational for both teachers and students. When using movies to help inspire students, teachers should first provide an age appropriate context and purpose for watching the film. For example, a teacher who has decided to show the film Hidden Figures in class might begin the discussion by providing a brief review of American politics in 1950s and 1960s. For example, teachers might ask students to revisit what they know about the desegregation of schools beginning in Little Rock in 1957. The teacher might emphasize how challenging it could be for African Americans during that time to receive the upper level education the characters in Hidden Figures needed to have. They might also be asked to reread work they did on Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique. Specifically, they might be asked to think about how women’s restrictive societal roles might influence women of that time to break norms and rules. In addition to understanding the political climate the movie’s protagonists faced, the teacher might provide students with a brief background of women computers in the 20th century. Students might be surprised and interested to learn that women have a long history of working for the government in crucial, mathematically-centered roles.

When provided with such context, teachers can easily provide a purpose for the film by focusing on ideals. During the course of the movie, students might be asked to write down the messages, or ideals, they believe the film delivers. For example, students might find the following relevant and inspirational messages:

-

Any person can achieve any goal they set through hard work and perseverance.

-

The ability to work as a part of a team can be life changing.

-

Setting an example by doing what is right can change history and create positive results on any project.

After students have articulated the ideals they feel the film focuses on, the teacher can ask students to more closely relate the film to their lives. Questions such as the following might be suitable:

-

Have you ever seen this ideal at work in your own life? How did you feel when times were difficult? Did you feel a sense of reward or accomplishment?

-

Can you describe an instance in your life where you felt like the movie’s ideals were lacking? (Maybe things just “weren’t like they are in the movies”?)

Teachers might record and reinforce students’ positive ideals throughout the year when appropriate.

The following is a list of contemporary movies commonly used to help inspire students:

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

Stories

Stories can also be sources of inspiration for students. There are many stories both online and in print that can serve as sources of inspiration for students of any age. Additionally, many different types of stories can be used. For example, a middle school teacher might choose the myths described in the Percy Jackson and the Olympians fantasy series as a source of student inspiration. After reading the books at their own pace, teachers might ask students to compare some of the story lines to events in their own lives or other story lines they have seen in real life. They might be asked to think about how similarities between the stories speak to common human goals and inspirations.

Conversely, teachers might use nonfiction stories as inspirational sources. For example, a teacher might ask students to read I am Malala by Malala Yousafzai. Each student might be asked to articulate the ideals they find exemplified in her story of perseverance. They might also be asked to provide specific passages that support the ideal they find to be inspiring, and they might be asked to explain why they feel the passage relates to their own lives.

The following is a list of individuals in contemporary society who might be considered inspirational:

JK Rowling

Desmond Tutu

Oprah Winfrey

Sean Swarner

Randy Pausch

Liz Murray

Temple Grandin

Liu Xiaobo

Nancy Herz

Chloe Kim

Quotations

Quotations that are memorable are often explicit or implicit statements of ideals. In this way, they can be great sources of inspiration for students. Additionally, because quotes are generally brief, teachers can incorporate them into lessons in a variety of ways. For example, teachers might simply read or display a quote at the beginning of class and let students ponder its meaning or ideal independently. Or, they might accompany the quote with brief information about the person to whom it is attributed—that information would relate directly to a unit the teacher is teaching or has recently taught. The quotes can also be used to help students consider inspirational themes a teacher may have chosen, such as: perseverance, independence, or overcoming obstacles.

Finally, Teachers can use quotes as key parts of lessons. For example, consider the following quote:

“Follow your inner moonlight; don’t hide the madness.” –Allen Ginsberg

While this quote seems simple, students might extract very different ideals and inspiration from it. For example, one student might choose to focus on the specific word “moonlight”. That student might note that the word connotes darkness and night. The student might interpret the quote as an ideal that expresses the need to cultivate and express even the darker, more negatives aspects of our nature. Conversely, another student might be curious enough to look up the context of the quote. He or she might find the interview in which the quote appears, and, after reading the entire interview, the student might determine that the ideal at the center of the quote focuses on the importance of speaking our own true minds no matter who might be listening. A rich discussion of ideals can follow from a quote.

Altruism

Depending on the situation, teachers can engage students in both long- and short-term projects that encourage altruism. Altruism can be defined as the principle or practice of helping others with no expectation of reward. Altruistic acts can help students understand how they can positively affect the world.

When focusing on altruism, teachers should be sure to refrain from rewarding students’ altruistic acts. Instead, after providing students with opportunities for altruism, teachers should ask students to simply reflect on the experience. Teachers can use the following questions to prompt reflection:

-

How do you think your actions affected others? What is an example?

-

What kind of insight do you think you gained from having positively affected someone’s life?

-

Has anyone ever done something kind for you with no expectation of thanks? How did you feel then? How do you feel about it now?

There are a variety of ways teachers can provide school-based, altruistic activities. Many schools are coordinating volunteer days throughout the year that teachers can encourage students to take part in. There are also many nation-wide events that encourage volunteerism on a set date. For example, events celebrating Earth Day (www.earthday.org), Make a Difference Day (http://makeadifferenceday.com), and Pay it Forward Day (http://payitforwardday.com). Teachers and students can also volunteer for local organizations or design their own service projects that are based on the unique needs of their communities.

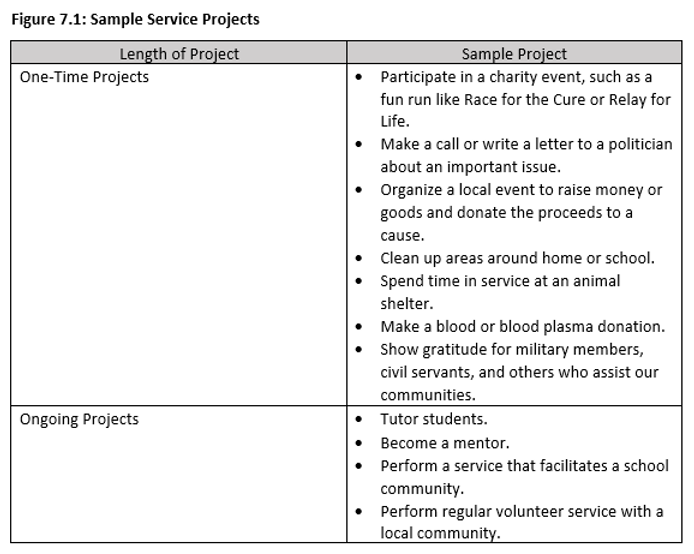

The effects of altruism can also be exemplified by example. Teachers can invite organizers of community events to speak about the effects local charities have on communities. Community members who benefit from volunteerism can also be asked to speak. Figure 7.1 describes some common altruistic projects.

Teachers can also provide students with specific examples of altruistic actions that have impacted communities. Teachers can consult local news sources or volunteer organizations that can help provide local examples. The following are additional relevant examples of altruistic actions as adapted from Lesli Amos (2014).

-

When she was only 15, Shannon McNamara started SHARE, an organization that provides girls in Africa with books.

-

Zach Certner founded SNAP, a program that focuses on developing athletic programs for children with special needs when he was only ten.

-

LuLu Cerone created LemonAID Warriors when she was ten. The program challenges other kids to make social activism a part of their social lives.

Empathy

Empathy is another pathway towards a connection to something greater than the self. Empathy helps us transcend our habits of focusing only on our own lives. However, students often need guidance on how to understand and practice empathy. Teachers must begin by instilling in students the difference between empathy and sympathy. While sympathy merely refers to someone’s ability to offer condolences or feel sorry for someone, empathy refers to one’s ability to use his or her own experiences in a way that relates to another person’s experiences, creating understanding and connection on a deeper level.

Examples of Empathy

Teachers can find a multitude of examples that exemplify empathy. Stories that were mined in real life or online as well as stories from history and literature can be incorporated into class time. Like quotations, these stories can be small daily lessons meant for individual reflection, or they can be the centerpieces for more in depth units.

For example, teachers may use small instances of empathy they have recently seen displayed as part of everyday conversation with students. Maybe a teacher has recently spoken with a friend who is caring for a loved one who broke a bone because he or she sustained a similar injury and can really understand how much help is necessary. A teacher might deliver a simple anecdote such as: “When my friend had surgery on his knee, he was unable to run each morning, and that really affected his mood and his ability to accomplish things during the day. Now that his grandmother has broken her hip, my friend visits her each day simply because he understands how difficult sitting still with an injury can be.” Teachers can ask students if there is anyone in their lives who is experiencing something they can empathize with.

Teachers can point out examples of empathy expressed in classroom assignments. For example, while reading the book Dad and the Dinosaur by Gennifer Choldenko, early elementary teachers might start a discussion about why the father in the book tries so hard to help his son find his lost and beloved dinosaur rather than just hug the boy and feel sorry that the dinosaur was lost.

Historical examples can also be used. For example, when reading about the potato famine of Ireland from 1845-1849, students might read different accounts of Queen Victoria’s actions. One account might focus on the Queen’s concerns that the famine would rally Irish nationalist movements, while another might describe her pleas to British politicians and her efforts towards raising money and contributing her own money to help alleviate the catastrophe. After reading the various accounts, students might be asked to think about the various levels of empathy described. They might be asked to consider how more empathetic accounts of Queen Victoria make her a more likeable historical figure. They might be asked to think about how displays of empathy affect other people’s overall opinions of a person’s character. Student can be asked to find their own examples of fictional and nonfictional accounts of empathy and sympathy. After finding examples, students might be asked to relate the terms to examples in their own lives.

Attributes of Empathy

When teachers ask students to understand empathy, it may be helpful to define specific characteristics, such as:

-

The ability to see the world from another person’s point of view.

-

The ability to see another point of view before judging another’s actions.

-

The ability to imagine another person’s feelings given a set of circumstances.

-

The ability to communicate an understanding of another person’s feelings, and taking that understanding into account when making relevant decisions.

(Adapted from Theresa Wiseman, 1996)

To help students understand the world as others see it, teachers might provide some guidance regarding the basic characteristics of empathy. For example:

-

Analyzing competing points of view: Debating or presenting given points of view (points of view that do not necessarily reflect the student’s own view) can help students understand multiple sides of the same issue.

-

Stepping outside their current circumstances: This might involve roleplaying as notable figures, or it might involve asking students to try to see the point of view of someone in their lives.

-

Explaining someone else’s reasoning: Students might be asked to choose a point of view expressed by someone they do not agree with. They might be asked to look more in depth at both the person and his or her views and try to explain why this person came to such conclusions.

To demonstrate being nonjudgmental, teachers might engage students in activities like the following:

-

Becoming aware of negative or judgmental language: For example, recognizing terms or phrases that indicate judgment in conversation (such as “I don’t like,” “I don’t understand,” or “I can’t believe”). When students can recognize judgmental language about both themselves and others, they can begin to eliminate judgmental thoughts and language and correct it when they can.

-

Discovering why judgments are often inaccurate: For example, understanding stereotyping and examining why the practice is simplistic and incorrect. When students recognize that judgments are often inaccurate, they may avoid making one and looking for additional information instead.

-

Identifying judgments they make or have made in the past: For example, students might be asked to think about judgments they hold. These could be in regards to a character in a book, a peer at school, a class or subject in school, or even a political issue. They may be asked to reflect on why they feel the way they do.

In order to help students learn how to understand another person’s feelings, the teacher might engage students in activities that facilitate the process. For example, teachers can:

-

Ask students to use targeted questioning: Teachers can ask students to pose internal questions such as: “If I were in this situation, how would I feel?” and so on. Target questions can help students focus on the feelings of another person rather than on their own feelings.

-

Ask students to explain how feelings affect interactions: For example, after explaining how feelings and emotions can affect one’s interpretations of a situation, teachers can ask students to choose examples from life, history, or literature in which someone’s feelings caused a skewed reaction to a situation.

-

Ask students to examine sympathetic feelings: For example, teachers might ask students to describe in detail what sympathetic feelings are. After providing some specific examples, students might then explain how those feelings might motivate empathetic behaviors.

-

Ask student to practice and read facial expressions: The subjects of photographic or artwork can provide students with excellent opportunities to practice identifying feelings.

In addition to understanding another’s feelings and points of view, students also need to be able to communicate and demonstrate their understanding. In this interest, teachers might engage students in the following activities:

-

Reflecting on their own language: For example, a teacher might ask students to think about recent conversations. What did they learn about someone? What questions did they ask? Also, what did you share about yourself? Students might be asked to think about whether they do more listening or sharing in a conversation.

-

Focusing on how others’ actions affect them rather than placing blame: For example, a teacher might ask students to simply make statements that fit the “When you __________, I feel ________” model.

-

Explaining empathetic qualities: For example, ask students to explain when they felt empathy was being expressed towards them and why. Students might say, “I knew you were paying attention to what I said because you asked questions that were based on my previous response.”

-

Reviewing reminders of appropriate communication: For example, teachers might refer to classroom procedures that outline appropriate communication and ask students to explain why those rules apply to all students.

Empathy

Forgiveness can also provide a connection to something greater than the self. Because forgiveness requires individuals to think outside of themselves, it can be intrinsically challenging for many, if not all people. Forgiveness can benefit not just the person being forgiven, but the person who has engaged in forgiveness as well. In schools, Elizabeth A Gassin, Robert D. Enright, and Jeanette A. Knutson (2005) posited that forgiveness can lead to a reduction in anger. Forgiveness leads to “less depression and anxiety and to stronger academic achievement and more peaceful social behavior” among students (p. 321).

Teachers can guide students by providing examples from real life, literature, or history. They can also ask students to consider who might need their forgiveness and who they might like to receive forgiveness from. Stories from resources such as The Forgiveness Project (www.theforgivenessproject.com) can provide powerful examples such as:

Scarlet Lewis’s son, Jesse, was killed in 2012 during the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting in Connecticut. In her grief, she found she had a lot of resentment for both the gunman and the mother Ms. Lewis believed had enabled him. Over time, she found that the anger and the resentment were overwhelming. One day, she saw a phonetically spelled message of nurturing and love her own son had left behind shortly before his death. She decided to make a choice of forgiveness, and her path led her to create the Forgiveness Project, an endeavor she helps will help bring others the kind of peace she has experienced through forgiveness.

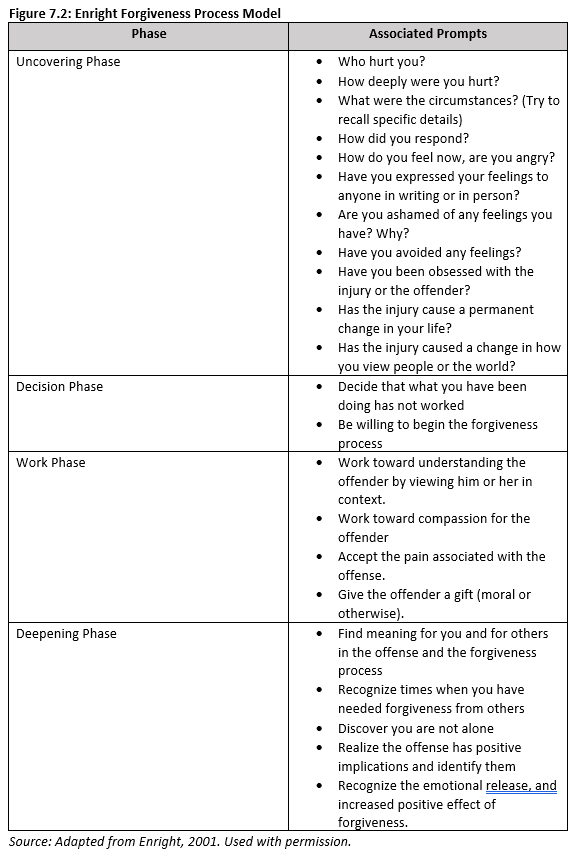

After students have processed such a story and discussed its inspirational attributes, teachers can more directly teach students about the process of forgiveness. A four-phase process might be introduced:

-

Uncovering phase: The recognition of an offense and its associated negative consequences.

-

Decision phase: Making the decision to forgive.

-

Work phase: Trying to reframe feelings or reach a deeper understanding of the offense or the offender.

-

Deepening phase: identifying the positives from the situation as a whole.

(Enright, 2001)

Figure 7.2 provides further guidance for teachers engaged in forgiveness instruction.

Gratitude also helps students connect to something greater than the self.

Researchers Jeffrey J. Froh and Giacomo Bono (2012) found that, for students, gratitude “improves their mood, mental health, and life satisfaction, and it can jumpstart more purposeful engagement in life at a critical moment in their development, when their identity is taking shape.” In general gratitude helps us see the positive aspects of our lives overall, and it helps us keep from focusing on a narrow perspective of one negative thing that might be happening in our lives. A good place to start regarding teaching students gratitude can be noted in the following broad statements:

-

The good experiences and feelings in life are as genuine as the bad.

-

The mere absence of the bad in life does not equate to an experience of the good.

-

What is good in life is worth acknowledging and exploring.

These statements allow students to begin exploring the practice of gratitude. Teachers might ask students after presenting these statements which of them they believe to be true and to what degree. Then, students working alone or in teams can generate definitions of gratitude. The following are some common examples that students might create.

-

Gratitude is being aware and appreciating the things that you value.

-

Gratitude is a good emotion, but it can be hard too. It means we realize that other people did a lot that cost them in many ways to help us—even if they didn’t know us.

-

Gratitude is that warm feeling we get when someone else has given us a piece of something they value.

-

Gratitude is appreciating how much other people have done to further our interests without furthering their own.

Students can also benefit from a systematic engagement in gratitude-based activities. Teacher can easily integrate the following gratitude activities identified by Vicki Zakrzewski (2013) into the classroom.

-

Gratitude book: A classroom scrapbook can make space for students to write and draw about things for which they are grateful. Families can contribute as well if the book is sent home with a different student each week.

-

Gratitude circle: Provide an opportunity for students to share what they are grateful me at the beginning or end of class. For younger students, examples may help stimulate conversation.

-

Gratitude collage or board: Teachers can create a bulletin board (physical or online) that allows students to post things which they are grateful for.

-

Gratitude journals: This, more direct exercise, asks students to think more in depth about things they are grateful for in their lives. Teachers may ask students to write about as many as three things they are grateful for. However, it is not recommended that students do this more than once a week.

-

Gratitude letters: To begin with, students might be asked to consider the jobs others do to help them in their own school. Janitors, food service staff, other teachers, peers, or administrators might be the subjects of initial gratitude letters. Members of the larger community who consistently serve us or specific people who have helped students might also be the recipients of gratitude letters.

-

Gratitude paper chain: A gratitude paper chain is a great way for students to see the overall effect of small actions. Students are asked to write one thing for which they are grateful on a small strip of paper. Those strips are then made into a paper chain that can decorate the room.

-

Gratitude quilt: A more visual version of the paper chain, students can draw things for which they are grateful on square paper. Those drawings can then be mounted on larger pieces of construction paper to create a border, and the squares can be assembled into a “quilt” that decorates the classroom.

-

Gratitude surprise sticky notes: Each student receives a number of sticky notes and is asked to write down one thing they are grateful for on each note. Students are then asked to display the notes in places where others will see them.

Gratitude activities can be executed without much planning, which makes them easy to use during any free class time.

Mindfulness

A modern definition of mindfulness is a deliberate focus on thinking that results in intentionality and/or action. These days, most people are so filled with plans, thoughts, and emotions that they are not able to fully notice what is happening around them, nor are they fully capable of making the best decisions. The simple act of being more aware of each moment often increases self-efficacy. Increasingly, mindfulness practice is being integrated into schools. For example, many schools have now adopted Quiet Time-type programs that ask students to reflect during a meditative-like practice for a set period of time during the day. Schools that have implemented two fifteen-minute periods of meditation during the school day have seen drastic changes in student behavior, one school noting the number of suspensions falling by 45% during the first year of the Quiet Time program (Kirp, 2014).

The following list presents strategies that help teachers present mindfulness to students in their classrooms (adapted from Patricia A. Jennings (2015)):

-

Mindful listening: Transition times can be difficult for students. Listening activities can help ease this. For example, when beginning a school day, teachers might ask students who are not yet ready to listen to sit still and close their eyes or lower their gaze to their hands. “Listen to your breathing, and try to take deep breaths. Listen for the sound of my bell, and keep listening until you don’t hear it anymore. Then, open your eyes and we can begin class,” a teacher might say. This can help students of all ages become more aware of classroom activities once instruction time begins.

-

Mindful walking: During class transitions or periods during which students appear to be restless, teachers can ask students to walk around the class, paying special attention to how they walk (e.g., the length and pace of their strides, how their feet hit the ground, or even how their shoes feel on their feet). Once students have been given this break from instruction and asked to tune in more, they may be more receptive to the lesson at hand.

-

Setting intentions: Ask students to set an intention each morning. An intention would be defined as something positive they intend to accomplish for the day. For example, making something positive out of something negative, or challenging oneself on an assignment or assessment. Teachers can ask students to reflect on those intentions as well, asking them to note whether or not the intention helped them accomplish the goal, or not if they accomplished a surprising goal.

-

Three breaths: This strategy can be used at any age. When students seem to need a break or seem overly anxious, teachers can ask them to place their hands on their chest and take three very slow, deep breaths. Be sure to ask students to feel their lungs fill and empty air. Ask students to reflect on how they feel after the exercise.

Each of these strategies can and should be adapted for different age groups. For example, an elementary teacher might simply ask students to think about what they would like to see happen over the course of the day and what they might do to make that happen. At the end of each day or each week, teachers might ask students to reflect on those desires and how their actions did or did not attribute to the desired result.

Recommendations

Teachers can and should use the strategies presented in this chapter in a variety of ways—any way that most suits their class and their students. We do recommend the following practices as a way to reinforce each strategy:

-

At least once a month present students with inspirational movie clips or stories and ask them to discuss the ideals they see presented.

-

Incorporate inspirational quotations whenever possible, even if this includes presenting the quotes with no comment.

-

Ask students to engage in an altruistic project at least once a year.

-

Use strategies that emphasize empathy, forgiveness, gratitude, or mindfulness at least once a semester.

Empower can be used to develop and archive instructional resources that help students learn about and practice the various aspects of inspiration.

Create Activity Video Create Activity One-Sheet

These can be reused and shared. We recommend you check out the Collaborative Work Article for more details on co-creating, sharing and searching.

Further Resources

Tutorial Videos

Print Resources

Sharing

Student Activity View

Control Panel

Exemplar: Primary School

Exemplar: Secondary School

Exemplar: Google Drive

Exemplar: Secondary ESL

Inbox

Personalized Competency Glossary

User Guide: Working Collaboratively

One-Sheet: Student Work

One-Sheet: Assigning Work

One-Sheet: Create Activities