XI. Knowledge Maps

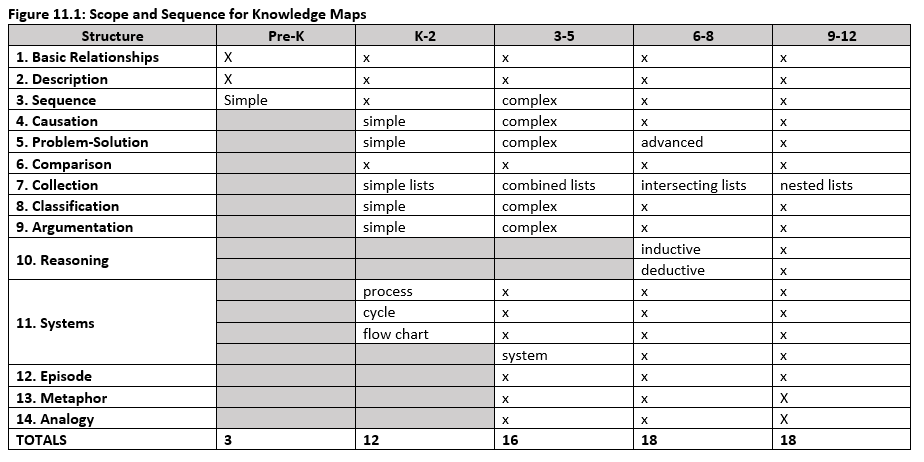

Knowledge maps represent common structures that students must recognize to read and understand information. They also represent common structures students must use to write well-structured and cohesive essays. These structures should be taught to students and then used as tools for comprehension and tools for writing. The knowledge maps academy teachers should use are listed in figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1 indicates that there are 15 different types of knowledge maps. A number of these maps have multiple forms that range from simple to complex. Also note that the figure depicts grade level bands within which specific types of maps are most appropriate.

One of the first things academy teachers must do is determine in which classes specific maps will be used. As depicted in figure 11.1, 12 maps are appropriate for use in grades K-12:

-

Basic relationships

-

Descriptions

-

Simple sequence

-

Simple causation

-

Simple problem solution

-

Comparison

-

Simple list

-

Simple classification

-

Simple argument

-

Process

-

Cycle

-

Flowchart

Teachers might determine that three of these structures should be taught at the Kindergarten level, five more at first grade, and four more at second grade.

1. Basic Relationships

The basic relationships knowledge map is meant to raise students’ awareness of how ideas relate to each other. When students pay attention to the types of connections between ideas, it strengthens their understanding and memory of the ideas and their relationship. Figure 11.2 shows the basic relationships knowledge map.

There are four types of basic relationships: (1) addition, (2) contrast, (3) time, and (4) cause.

Addition relationships indicate that things are alike or the same, and are signaled by words such as and, additionally, as well as, likewise, that is, in fact, for example, in sum, overall, and together. Addition relationships are typically focused on connecting items that belong in the same category. For example, the following sentences identify a category and items that fit in that category.

• Jane has three pets: a cat, a dog, and a fish. (category: pets; members: cat, dog, fish)

• We read about famous baseball players, like Babe Ruth. (category: famous baseball players; member: Babe Ruth)

• Sam exercised a lot today! He did push-ups, lifted weights, and ran four miles. (category: exercise; members: push-ups, weights, running)

Addition relationships are also present when the same idea is presented twice, in slightly different ways. For example, in the sentences, “I love to read. In fact, reading is my favorite activity.” the idea being communicated is a preference for reading; the author is simply expressing such an idea in multiple ways. That is, both of the statements belong in the category of “statements that express a preference for reading.”

Contrast relationships indicate that things are opposite or different, and are signaled by words such as but, on the other hand, rather, alternatively, in contrast, in comparison, however, in spite of, and nevertheless. Contrast relationships are focused on distinguishing items that belong in different categories. For example, the following sentences identify a category and items that do not fit in that category.

• I like pizza but I don’t like salad. (category: food I like; nonmember: salad)

• Tony must either vacuum the floor or put the dishes away. (category: chores Tony must do; potential nonmember #1: vacuum, potential nonmember #2: put dishes away)

• Anna has red hair but mine is brown. (category: Anna’s hair color; nonmember: brown)

Contrast relationships are also used to pair two ideas that don’t go together. For example, in the sentence, “My brother is really annoying, but I love him anyway.” the author is saying that her brother is annoying (which makes us think she doesn’t like him) but that, in spite of his annoying behaviors, she loves him anyway.

Time relationships talk about when things happened, and are signaled by words such as before, after, while, later, earlier, until, in the meantime, and meanwhile. For example, the following sentences express things happening at the same time, before other events, or after other events.

• It is summer in the northern hemisphere while it is winter in the southern hemisphere.

• We waited for fifteen minutes before my friend showed up.

• I didn’t understand until after the teacher explained the math problem.

Cause relationships talk about why things happened, and are signaled by words such as because, as a result, consequently, thus, so, and hence. For example, the following sentences express a cause and an effect.

• The flying rock made a hole in the window. (cause: flying rock; effect: hole in window)

• I got sunburned because I didn’t wear sunscreen at the pool. (cause: no sunscreen; effect: sunburn)

• If we go to the mall, I will buy a pair of shoes! (cause: going to the mall; effect: buying shoes)

Once students have been taught the basic relationships maps they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can ask students to examine a short passage and identify the more obvious basic relationships in the passage. They can create diagrams that depict those relationships, rewrite the ideas in abbreviated form, and use the symbols to signify the type of relationship between various sets of ideas.

Writing

Teachers can ask students to write short paragraphs that follow a specific pattern of basic relationships. For example, a teacher might provide students with a starting sentence and then ask them to create two sentences that have addition relationships with that sentence, followed by one sentence that has a contrast relationship.

2. Description Structures

Description structures list characteristics of an item. Items can include people, places, objects, animals, or processes. Figure 11.3 shows the description knowledge map.

Especially in narratives, description structures often feature sensory details that describe what something looks like, sounds like, smells like, tastes like, or feels like. For example, in Charlotte’s Web, E. B. White describes what the Zuckerman barn feels like, looks like, and smells like, as shown in figure 11.4.

In informational texts, description structures usually give facts about an item. For example, in Gail Gibbons’ The Moon Book, she uses a description structure to share the following facts about the moon:

• Brightest and biggest light in the night sky

• Only moon of Earth

• About 238,900 miles away

• Reflects the sun’s light

• About ¼ the size of Earth

• Make of rock and dust

• No air or sign of life

• In ancient times, people believed the moon was a god or goddess

• Romans – Diana

• Greece – Selene

• Native American tribes – sibling of the sun god

Once students have been taught description maps they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative and expository texts that have explicit or implicit description structures. Students would be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the description structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized as a description structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the map and then generate a rough outline of a composition using the map. Students would then generate the composition from the outline.

3. Sequence

A simple sequence structure lists events in order. Most narratives use an overall sequence structure. Figure 11.5 shows the simple sequence knowledge map.

Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are features a simple sequence structure. The following series of events is recounted:

1. Max makes “mischief of one kind and another.”

2. Max’s mother calls him “WILD THING.”

3. Max says “I’LL EAT YOU UP.”

4. Max is sent to bed without supper.

5. A forest grows in Max’s room and an ocean with a private boat appears.

6. Max sails off “through night and day and in and out of weeks and almost over a year” to where the wild things are.

7. Max tames the wild things and becomes king.

8. The wild rumpus happens.

9. Max is lonely.

10. He sails home.

11. Supper is waiting, and it is still hot.

Sequence structures also show up in informational texts. Often, an informational text will tell about a later event in a sequence and then go back and fill in earlier events (which also relates to causation structures). For example, Tanya Lee Stone’s The House That Jane Built, describes how Jane Addams founded Hull-House in Chicago in 1889, and it features the following sequence of events:

1. Jane, a wealthy young woman, moves into one of the poorest neighborhoods in Chicago.

2. At 6 years old, Jane goes on a trip with her father and notices different social classes.

3. She vows to find a way to help poor people.

4. She demonstrates bravery (exploring caves, finding owl nests) as she grows up.

5. She demonstrates intellect as she grows up.

6. She goes to college.

7. Her father dies and Jane feels lost.

8. Jane travels to London and sees poor people again.

9. She visits Toynbee Hall, a settlement house in London (where rich and poor people live together in a house).

10. She decides to build a settlement house in Chicago.

11. She opens Hull-House.

A fiction example is William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. It tells the same story four times, from four characters’ points of view:

• Benjy

• Quentin

• Jason

• Dilsey

A nonfiction example might be an article about the events of World War II. It might use the complex sequence map to describe events that occurred in North America, Asia, Europe, and Africa during the war, as shown in figure 11.7.

A complex sequence organizer could reveal that most of the events of World War II happened in Asia and Europe.

Once students have been taught sequence maps appropriate to their grade level, they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

A teacher might ask students to read narrative and informational texts that contain implicit and explicit sequence structures. Students would be asked to diagram the elements of the simple or complex structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized in simple or complex sequence structures. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition using the maps. Students would then create a composition from the outline.

4. Causation

A simple causation structure shows the causes and effects of an event. Figure 11.8 shows the simple causation knowledge map.

As mentioned previously, Tanya Lee Stone embeds a causation structure in the overall sequence structure of The House That Jane Built, as shown in figure 11.9.

Another informational text example is Mary Batten’s Aliens from Earth: When Animals and Plants Invade Other Ecosystems. It highlights relationships between the following invasive species and the areas where they were introduced.

• Effect of the gypsy moth on the United States

• Effect of rabbits on Australia

• Effect of pigs and mosquitos on Hawaii

• Effects of fire ants on the United States

A fiction example is Laura Numeroff’s If You Give. . . series, which includes:

• If You Give a Mouse a Cookie

• If You Give a Moose a Muffin

• If You Give a Pig a Pancake

• If You Give a Cat a Cupcake

• If You Give a Dog a Donut

The structure in each book forms a circle with the last event causing the first event in the book to occur again. For example, in If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, (1) giving the mouse a cookie causes him to ask for milk to go with it, (2) which causes him to have a milk mustache, (3) which causes him to need to look in the mirror to clean it off, (4) which causes him to think he needs a haircut, (5) which causes him to ask for scissors to cut his hair, (6) which causes him to become so tired that he needs a nap, (7) which causes him to ask for a story, (8) which causes him to want to draw a picture, (9) which causes him to want to hang his picture on the refrigerator, (10) which causes him to remember he is thirsty, (11) which causes him to ask for milk, (12) which causes him to ask for a cookie to go with it.

A complex causation structure involves extra causes and effects that aren’t part of the main causal chain, but branch off from it. Figure 11.10 shows the complex causation knowledge map.

For example, a text describing causes and effects of the Stock Market Crash of 1929 might use a complex causation structure to organize the events, as shown in figure 11.11.

Once students have been taught causation maps appropriate to their grade levels, they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit causation structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the causation structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a causation structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition using the maps. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

5. Problem/Solution

A simple problem-solution structure presents a problem and several potential solutions, indicating the best solution. Figure 11.12 shows the simple problem-solution knowledge map.

A simple problem-solution structure presents a problem and several potential solutions, indicating the best solution. Figure 11.12 shows the simple problem-solution knowledge map.

Another fiction example is the Mrs. Piggle Wiggle series by Betty MacDonald. Each chapter presents a different problem. For example:

• Hubert Prentiss won’t pick up his toys

• Mary O’Toole answers back

• Dick Thompson won’t share

• Patsy Waters won’t take baths

• The Grey children won’t go to bed

The children’s parents always try several potential solutions, which never work, before calling Mrs. Piggle Wiggle. Mrs. Piggle Wiggle suggests the best solution, which then cures each child of his or her problem.

Problem-solution structures in informational texts typically occur in articles that advocate for a specific solution. For example, the article “Should We Tax Robots That Take Our Jobs?” on newsela.com addresses the problem, “When employers replace human workers with robot workers, the government loses the income tax they would have collected from the human worker’s wages.” It offers three potential solutions:

1. Estimate what a human worker would make doing the same job as a robot and charge the employer a tax based on the robot’s hypothetical “salary.”

2. Charge employers a one-time “sales tax” when they buy a robot to replace a human.

3. Transfer some ownership of a company that uses robots instead of human workers to the government and use profits from the government-owned part of the company to replace the income tax that would have been collected from a human worker.

The author of the article, Yanis Varoufakis, a former finance minister of Greece and now a professor of Economics at the University of Athens, advocates for solution 3.

A complex problem-solution structure adds criteria that are used to evaluate the solutions. Figure 11.14 shows the complex problem-solution knowledge map.

For example, the article “Environmentalists Are Not In Favor Of Government-Planned Fish Farms” on newsela.com addresses the problem of commercial fishing threatening fish populations worldwide. It offers three potential solutions:

1. Establish man-made fish farms on land.

2. Establish fish farms close to shore using natural and man-made elements.

3. Establish off-shore fish farms in the open ocean.

It also offers criteria for judging each solution.

• Impact on the environment

• Impact on the U.S. economy

• Legislative approval

An advanced problem-solution structure weights each of the criteria. Figure 11.15 shows the advanced problem-solution knowledge map.

In the previous example, addressing the threat of commercial fishing to worldwide fish populations, the following weights might be assigned to each of the criteria.

• Impact on the environment – 2 (somewhat important)

• Impact on the U.S. economy – 1 (least important)

• Legislative approval – 3 (most important)

Once students have been taught problem-solution maps appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit problem-solution structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the problem-solution structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a problem-solution structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

6. Comparison

A comparison structure uses several characteristics to compare several items. Figure 11.16 shows the comparison knowledge map.

For example, students could compare versions of the Cinderella story from around the world:

• Africa: Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters by John Steptoe

• Native American: Rough-Face Girl by Rafe Martin

• Asia: Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story from China by Louie Ai-Ling

• Europe: Tattercoats: An Old English Tale by Diane Goode

• Central America: Adelita: A Mexican Cinderella Story by Tomie DePaola

These different versions could be compared according to characteristics such as:

• Cinderella’s family members

• Mistreatment of Cinderella

• Important ball or dance

• Role of a shoe or slipper

• Identity of the prince

• Ending of the story

Informational texts include Lisa Bullard’s What’s the Difference… series. These books compare similar but different animals, such as the alligator and crocodile, or the turtle and the tortoise. Sneed Collard’s Teeth compares the functions of different animals’ teeth.

Once students have been taught comparison structures appropriate to their grade level they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit comparison structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the comparison structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a comparison structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

7. Collection

Collection structures are lists. There are four different kinds of lists:

• Simple list

• Combined list

• Intersecting list

• Nested list

A simple list is a collection of items that fit in a category. Figure 11.17 shows the simple list knowledge map.

Recall from the description of Zuckerman’s barn from E.B White’s Charlotte’s Web the list of items found in the barn:

• ladders

• grindstones

• pitch forks

• monkey wrenches

• scythes

• lawn mowers

• snow shovels

• ax handles

• milk pails

• water buckets

• empty grain sacks

• rusty rat traps

An informational text example is Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin by Lloyd Moss; it lists the following musical instruments:

• Trombone

• Trumpet

• French horn

• Cello

• Violin

• Flute

• Clarinet

• Oboe

• Bassoon

• Harp

A combined list pairs a collection of items with data for each item. Figure 11.18 shows the combined list knowledge map.

At the end of Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin, the text provides three categories into which the instruments can be organized:

• Strings

• Reeds

• Brasses

• Woodwinds

The instruments could also be paired with data about their typical pitch range: high-, medium-, or low-pitched. Therefore, a combined list for the instruments, their category, and their range would likely look like that shown in figure 11.19.

An intersecting list eliminates redundancy in a combined list. Figure 11.20 shows the intersecting list knowledge map.

With the previous musical instrument example, an intersecting list might show types of instruments as row headers and pitch ranges as column headers, as shown in figure 11.21.

A nested list allows the creation of an intersecting list that contains more than three sets of information. Figure 11.22 shows the nested list knowledge map.

A student might want to add data pertaining to how the various instruments are played (bowing, plucking, blowing, striking). He or she might also want to indicate which type of group (symphony orchestra, marching band) the instrument is typically played in. And the student might want to add instruments that are not necessarily featured in Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin. Such an endeavor might result in a nested list like the one in figure 11.23.

Once students have been taught collection maps appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit collection structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the collection structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a collection structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

8. Classification

A simple classification structure is used to sort items into categories. Figure 11.24 shows the simple classification knowledge map.

A large circle represents the category and items that meet the requirements for membership in the category are placed within the circle.

A complex classification structure is present if more than one category is used for classification. Figure 11.25 shows the complex classification knowledge map.

Multiple large circles are used to represent the categories. Categories can be nested within other categories. Rochelle Strauss’ Tree of Life: The Incredible Biodiversity of Life on Earth uses the kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species classification structure to present information about various organisms.

Once students have been taught classification maps appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit classification structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the classification structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit classification structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the classification structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a classification structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

9. Argumentation

For younger students, a simple argumentation structure involves articulating an idea and explaining why they think their idea is a good one. Figure 11.26 shows the simple argumentation knowledge map.

For example, a student might claim that all kids should play sports and give the following reasons (grounds):

• Playing sports helps you learn teamwork.

• Sports give you exercise which is healthy.

• Sports are a lot of fun to play.

Or, as another example, a student might claim that kids should choose their own bedtimes and give the following reasons (grounds):

• Kids will learn to take care of themselves better.

• Kids will have more time for homework and reading.

• It will be easier for kids to fall asleep if they go to bed when they feel tired.

A great book to illustrate this is Mo Willems’ Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus. The pigeon wants to drive the bus and gives many reasons why he should be allowed to do so.

For older students, a more complex argumentation structure, involving grounds, backing, and qualifiers to support a claim, is likely more appropriate. Figure 11.27 shows the complex argumentation knowledge map.

For example, such a structure might be used to analyze the argument presented in the article “Should Washington, D.C., become a state? Its mayor says yes” on newsela.com. A claim is a new or controversial idea. For example, the claim of the article is that Washington DC should become a state.

Grounds are the reasons for the claim, often signaled by the word because. For example, Washington DC should become a state because its population is bigger than some states’, and it pays more government taxes than many states.

Backing is evidence to support the grounds. For the grounds “its population is bigger than some states,” backing could be a chart showing the population of various states and the population of DC arranged in ascending or descending order to show where DC falls. For the grounds “it pays more government taxes than many states,” a similar chart could show how much various states and the District pay in taxes.

Qualifiers are additional information that may not support a claim. For example, it is interesting to note that the mayor of Washington DC, who wants the District to become the 51st state, is a Democrat. This is interesting because most of the people who live in DC are Democrats, so if it became a state with that ability to elect legislators, the Democratic party would become stronger. So, while there may be good reasons for DC to become a state, the mayor may also be acting in the interests of her political party.

Once students have been taught argumentation maps appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools in reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit argumentation structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the argumentation structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into an argumentation structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

10. Reasoning

There are two types of reasoning structures: inductive and deductive.

Inductive reasoning structures begin with a set of concepts (from the same category) and a series of questions (about the concepts). The goal of inductive reasoning is to make a claim.

Students apply each question to each concept and write their observations in the appropriate cells. Then they draw conclusions about each concept, conclusions about each question, and finally formulate a claim. For example, if students were examining the following types of mathematical operations:

-

addition

-

subtraction

-

multiplication

-

division

-

An individual activity regarding these operations would be one in which someone analyzes these operations with the intent of generating new conclusions about the operation. To do so, the individual might ask the following questions about each operation:

-

What is happening? (combining or separating)

-

How is it happening? (by item or by group)

-

What properties apply? (distributive, associative, commutative)

The last three columns in figure 11.28 represent observations about the four operations generated by the question. The inductive conclusion would be a statement that is not explicit in the observations but is supported by the observations. The following would be an inductive conclusion:

-

The four operations can be arranged in a 2x2 matrix; each operation is most like the ones it touches.

-

the properties apply to combining situations

Deductive reasoning structures begin with a situation and a possibly applicable generalization or principle. If certain conditions are met, the generalization or principle can be used to predict or make a claim about what will happen in the situation. For example, the situation might be growing a class garden. The possibly applicable generalization or principle might be “if you plant seeds in the ground, they will grow into plants that produce food.”

The conditions that must be met for this principle to apply might include:

-

the seed is planted at the correct time of year

-

the seed is planted at the correct depth

-

the seed is left alone and allowed to germinate (that is, nothing digs it up or eats it)

-

the seed gets adequate sunlight and water

-

the type of seed planted typically grows in the climate of the garden (tropical, temperate, arctic)

-

the soil has the nutrients needed for the plant to grow

In one case, if tomato seeds are planted in good soil in the spring in a hot, humid climate and are given adequate water and sunlight, plants will probably grow and bear fruit during the summer months. However, if tomatoes are planted in the winter in an arctic climate and are not tended, it is unlikely that they will grow into plants or bear fruit.

Once students have been taught reasoning maps appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools for reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit reasoning structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the reasoning structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a reasoning structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

11. Systems

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a reasoning structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

A process is a set of steps that does not repeat. For example, most recipes are processes. You follow a set of steps to arrive at a final product.

A cycle is a set of steps that repeats. For example, the life stages of many insects occur in cycles. A butterfly lays an egg, it hatches, the caterpillar eats and then forms a chrysalis, emerges as a butterfly, lays an egg, and the process repeats. Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar is a good book to illustrate this for very young children.

Flow charts are used to keep track of a sequence of decisions that lead to other decisions. For example, a flow chart can be used to find errors in an argument. A student might begin by asking:

-

Is the information being presented important or trying to persuade me?

If it is, they would analyze it for errors. If it isn’t, they might exit their analysis; if information is unimportant or not intended to persuade, analyzing it for errors might not be a smart use of time.

Additional steps might include:

-

Does anything seem wrong about this information? If no, stop analysis.

-

If yes, what type of error might be present?

Each type of error could have its own flow chart to help students isolate exactly where the faulty reasoning of an argument lies.

A complex system involves multiple parts that interact with and affect each other. This structure can be found in many places:

-

Nuclear reactors

-

Earth’s climate

-

Human brain

-

Ecosystems

-

Cells

-

Cities

-

Businesses

-

Plot structures

Analyzing a system involves figuring out what will happen to other parts if one part is modified or eliminated.

An entertaining example to illustrate a system is to think about the characters in the fairy tale Cinderella: stepmother, stepsisters, prince, and Cinderella herself. A system structure can be used to diagram how they all feel toward each other.

Once students have been taught system structures appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools in reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit systems structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the systems structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized as a description structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the map and then generate a rough outline of a composition using the map. Students would then generate the composition from the outline.

12. Episode

The episode structure can be used to tell or analyze a narrative. Narratives might be fictional, historical, or personal. In the book, Baseball Saved Us, author Ken Mochizuki uses an episode structure to relate his boyhood experiences in a Japanese internment camp during World War II.

Cause: United States at war with Japan; U. S. government said that it could not tell who might be loyal to Japan

Effect: Son learns to have an internal sense of worth and cope with discrimination and prejudice

Time and duration: 1942-1945

Place: Internment camps in the middle of American deserts

Characters:

-

Dad

-

Mom

-

Son

-

Big brother Teddy

-

Soldiers with guns

-

Man in the tower

-

Older people

-

Other moms

-

People back home and at school after being released

Events:

-

Had to move away from home

-

Lived in horse stalls

-

Bad living conditions; no privacy

-

Older people have nothing to do

-

Brother becomes disrespectful

-

My dad decided to build a baseball field

-

Camp inmates work together to build baseball field

-

Moms make uniforms

-

Son isn’t very good

-

Inmates play baseball together

-

Last game of the year

-

End of the game

-

Guard watching makes son mad

-

Son hits a home run

-

Guard smiles at son

-

-

Inmates are released and return home

-

Son still experiences discrimination and prejudice

-

Son is a good baseball player and it helps him stand up for himself

Once students have been taught episode maps appropriate for their grade levels they can use them as tools in reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit episode structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the episode structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into an episode structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

13. Metaphor

Metaphor structures compare two items. A metaphor structure can be used to analyze a metaphor, such as love is a rose or it can be used to compose a metaphor for a concept, such as leadership.

To analyze a metaphor, students might match characteristics of each item that have abstract attributes in common. For example, love can be lost easily and a rose can be damaged easily. In the abstract sense, both are fragile.

To compose a metaphor, students might begin by articulating the characteristics of one item. For example, a good leader:

-

Is able to see things others can’t see

-

Faces difficult situations bravely

-

Doesn’t give up easily

-

Likes big challenges

-

Take responsibility for their own accomplishments, and not the accomplishments of others

-

Adapts to changing conditions and circumstances

-

Trains people to take his or her place

In the abstract, those characteristics might be stated as:

-

Great vision

-

Fearless

-

Tenacious

-

High-achievers

-

Responsible

-

Flexible

-

Reproduces himself or herself

The student then tries to think of another item that possesses those same abstract characteristics. In this case, they might think of an eagle, which has the following characteristics that correspond to the abstract characteristics of a good leader:

-

Is able to see things that other birds can’t see

-

Will fight birds and animals much larger than itself

-

Doesn’t fly away from storms, just flies higher

-

Fly up to altitudes of 10,000 feet

-

Catch their own meat; they aren’t scavengers

-

They adapt to changing wind currents and weather conditions

-

Raise young eagles, teaching them to fly and hunt

Once students have been taught metaphor maps appropriate for their grade levels they can use them as tools in reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit metaphor structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the metaphor structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into a metaphor structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

14. Analogy

An analogy structure features pairs of items that are connected by a particular type of relationship. For example, a movie might affect your emotions in the way that a roller coaster affects your body. In this case, there is a causal relationship between the movie and your emotions and the roller coaster and your body; one causes the other to feel shaken up and disoriented.

Here are some other examples:

-

As a sword is the weapon of a warrior, the pen is the weapon of a writer. (function relationship)

-

As a detective investigates crimes, a doctor diagnoses diseases. (function relationship)

-

As nails grate on a chalkboard, your voice grates on my ears. (function relationship)

-

As a caterpillar emerges from its cocoon, she stepped out of her comfort zone. (time/sequence relationship)

There are about six other types of relationships that might be featured in an analogy:

-

Synonyms

-

Twelve is to a dozen as three is to a trio.

-

-

Antonyms

-

Hot is to cold as day is to night.

-

-

Shared category

-

Knife is to fork as pen is to pencil.

-

-

Category and member

-

Eating utensil is to fork as writing utensil is to pencil.

-

-

Size

-

Ant is to elephant as cottage is to mansion.

-

-

Whole-part

-

Foot is to human as wheel is to car.

-

One of the main benefits of thinking about metaphor and analogy structures is that it stimulates divergent thinking. Convergent thinking seeks consensus; divergent thinking seeks creativity and alternate interpretations.

Once students have been taught analogy maps appropriate to their grade levels they can use them as tools in reading and writing.

Reading

Teachers can present students with narrative or expository texts that have implicit or explicit analogy structures. Students might be asked to identify and diagram the elements of the analogy structure. They would also be asked to summarize the passage using the information in the structure.

Writing

The teacher might present students with content that can be organized into an analogy structure. Students are then asked to diagram the content using the maps and then generate a rough outline of a composition. Students would then generate the composition using the outline.

Hierarchical Structures

Texts that are relatively long will commonly include hierarchical patterns. This means that the passage will have an overarching structure that organizes all or the majority of the content and will have embedded structures at a number of levels. This is depicted in figure 11.38.

This diagram represents a passage, the overarching structure for which is comparison, let’s say between two national monuments such as the Statue of Liberty and Mount Rushmore. The passage begins with descriptive structures for each. However, the next structure for one national monument is a sequence structure and for the other it is a causation structure. The next structure under sequence is episode, and the next structure under causation is sequence.

Students can be asked to create passage diagrams like the one in figure 11.37 when they read complex texts. After they write compositions students can be asked to create similar diagrams as a vehicle for analyzing their own writing.

Student Choice

As a powerful reading activity, teachers might ask students to read a passage using a knowledge map of their own choice. The teacher might provide them with one or more options. Students would select one map and fill it in using content from the passage. They would then defend their selections.

To illustrate, a teacher might provide students with a passage that discusses Copernicus’s discovery of the heliocentric model in detail. He or she might present the students with the following five knowledge maps:

-

Description

-

Comparison

-

Problem/Solution

-

Episode

-

System

One student might select the comparison map. She might use the comparison structure to highlight the similarities and differences between the heliocentric and the geocentric models of the universe. Another student might select the episode map. For him, the politics and attitudes that were contemporary in Copernicus’s time were key to the scientific community’s acceptance of the model. Finally, a third student might use the problem/solution map to illustrate why the heliocentric model ultimately came to prominence and what problems it solved.

Empower can be useful in providing resources that explain and exemplify the various cognitive structures.

Relative to using knowledge maps within Empower, academy teachers should know how to develop playlists that explain and exemplify each knowledge map.